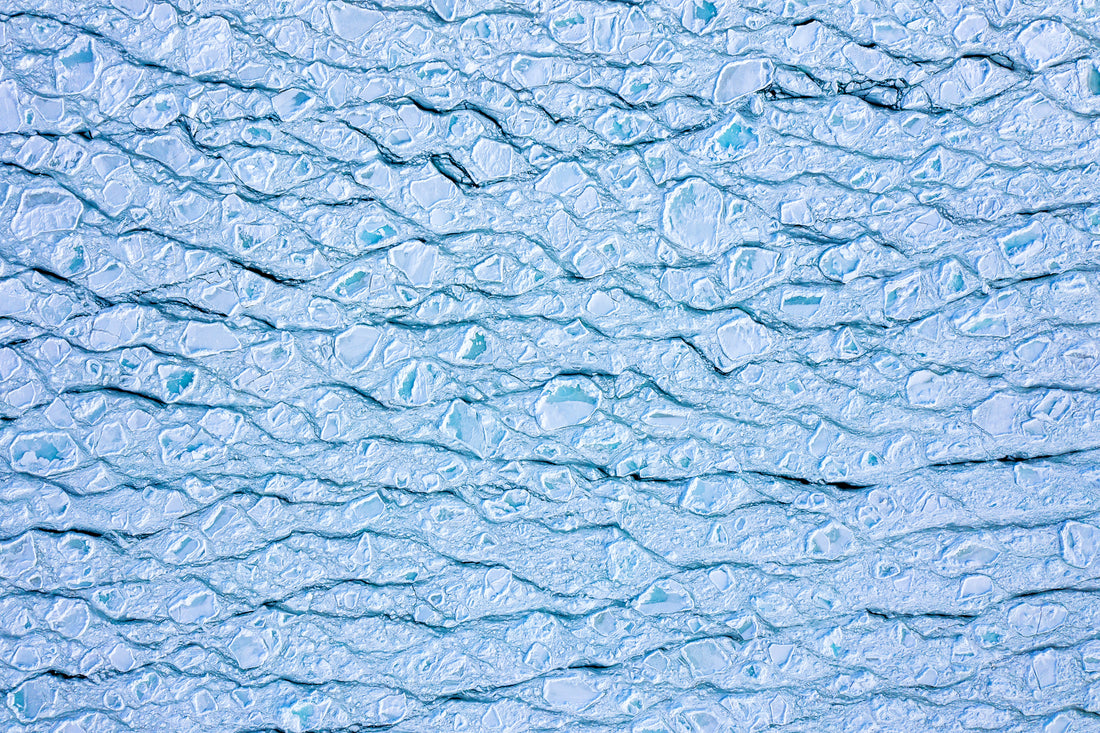

Beyond the shores of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island stretching up to Russia’s Sakalin Island, an awe-inspiring transformation is taking place — one an untrained eye would have thought reserved only for the likes of mystical epics. What starts as an icy serpent, descending south, plunges into the sea and expands into a frozen coulee of sea ice covering some 1,000,000 sq/km in a thick, suffocating layer of floating pancake ice.

-

As winter descends upon the islands of Hokkaido, plunging temperatures to a punishing average of -30°C, the island’s flourishing farmlands morph from a tapestry of colour and fertility to a vast canvas of white. Once a fertile hub of agricultural activity, come winter the island transforms into a glacial fortress deeply at odds with the spring and summertime scenes of prosperity which precede it.

As the island enters its long, stark winter, the mountains, dotting the island, are consumed by snow and seared by harsh arctic winds, while the forests shed their summer canopy and stand exposed to winter’s cold caress.

-

From January each year the fertile seas of the north — rich with ocean life and teaming with birds and fish of all kinds through summer — begin their Arctic change, possessed by the bracing grip of the sea ice, or Ryūhyō as it’s known in Japanese. The Ryūhyō begins its serpentine journey swirling across the Okhotsk sea, enveloping Sakalin Island before migrating south with the currents to Northern Hokkaido. Here, ever growing and all-consuming, it engulfs the coastline, solidifying its harbours and covering the beaches with chunks of frozen white magma.

Contrary to popular belief, drift ice is not a product of extreme winter temperatures simply freezing the ocean. Instead the ice is born in the deep Russian Arctic and carried down into the Sea of Okhotsk by the Amur River – the tenth longest in the world, sandwiched between the Chinese-Russian border. As fresh water from the river enters the Sea of Okhotsk, it lowers the salt concentration causing the water to freeze, forming drift ice. Through the months of January and February, a magnificent expanse of white pancake ice disks, collected together in a gently moving oceanic slushy, blanket almost the entire Sea of Okhotsk to envelop the northern coastline of Hokkaido.

From the northern corner of Wakkanai across Hokkaido’s northern coast, filling the harbours of Monbetsu and Abashiri, this glacial beast forces itself eastward to collide with the Shiretoko Cape – protruding out from the the north eastern corner of Hokkaido like a jagged blade.

Known to the indigenous Ainu people native to Hokkaido as ‘the end of the earth’, Shiretoko indeed feels like the precipice of existence. An enormous cluster of mountains rising from the ocean like jutting cliffs, this momentous Cape is lined with volcanoes and cloaked by white ice stretching as far as the eye can see during the long winter months.

It is here at land’s end where the ice is at its most concentrated and dense, a fact only adding to the harsh magnificence of this Arctic limb. To look at, this bewitching, desolate expanse of white is breathtaking, a testament to nature’s majestic, powerful hand. It’s therefore difficult to imagine how any form of life might survive beneath — or above — such an icy climate, but it is thanks to the winter-long presence of Ryūhyō at Shiretoko Cape that the peninsula is in fact home to a thriving ecosystem. Indeed UNESCO designates the Cape as having an “extraordinary ecosystem productivity” due to to “the supply of nutrient-rich intermediate water resulting from the formation of sea ice in the Sea of Okhotsk, [allowing] successive primary trophic productions including blooms of phytoplankton in early spring.” Thus from its shores visitors can glimpse the likes of sperm whales and beaked whales, as well as Pacific dolphins and porpoises and endangered birds such as white-tailed eagles and Blakiston’s fish-owls.

The northeastern coastline of Hokkaido stretches over 400 km with a few major towns dotted along the meandering road that runs from Wakkanai to Shari and the Shiretoko Peninsula. Probably the most noteworthy of these is Abashiri, a small, humming city of around 40,000 people and business hub on the Sea of Okhotsk. The city is cold yet friendly in winter and in summer its pulse rises to an energetic beat as the surrounding farms and fishing industries kick into full swing after a frozen winter.

At some 75 km from the Shiretoko National Park, Abashiri makes for an ideal base from which to explore Hokkaido’s breathtaking east coast and is the primary gateway to witness the natural wonder of Ryūhyō cloaking the Sea of Okhotsk. Those keen to learn more about drift ice can visit Abashari’s Okhotsk Ryūhyō Museum, something of a testament to the wonder and cultural importance attributed to Hokkaido’s drift ice, even if reviews might hint at it a certain gimmickiness. Yet nothing can come close to visiting the sea ice up close and personally to experience another jewel in the crown of Hokkaido’s natural wonders.

More From The Journal

View All-

Conversations

Photographer Reylia Slaby on her visceral work that explores culture and identity

Speaking to the Nara-based artist, we sought to understand what makes her tick, and why she turned to Fine Art photography.

-

Travels

Rishiri Island — Skiing in Lands Unknown

Situated some 20 km west of Hokkaido sits the small, disk-like island of Rishiri. Small and compact it may be, yet this mighty little island packs a punch, for standing tall and fierce in the rotund island’s icy centre is Mount Rishiri.

-

Conversations

Shaping Surfboards with Craftsman John Carper

A shaper by trade, JC has years of experience designing and constructing boards for notable

brands and individuals in the sport.